Four boys are forcibly removed from home, and a convoluted postal forwarding infrastructure reveals their systemic isolation from their parents and tribe

[Cultural Genocide] [Native American Boarding Schools] [Family Separation] Methodist Shawnee Manual Labor School.

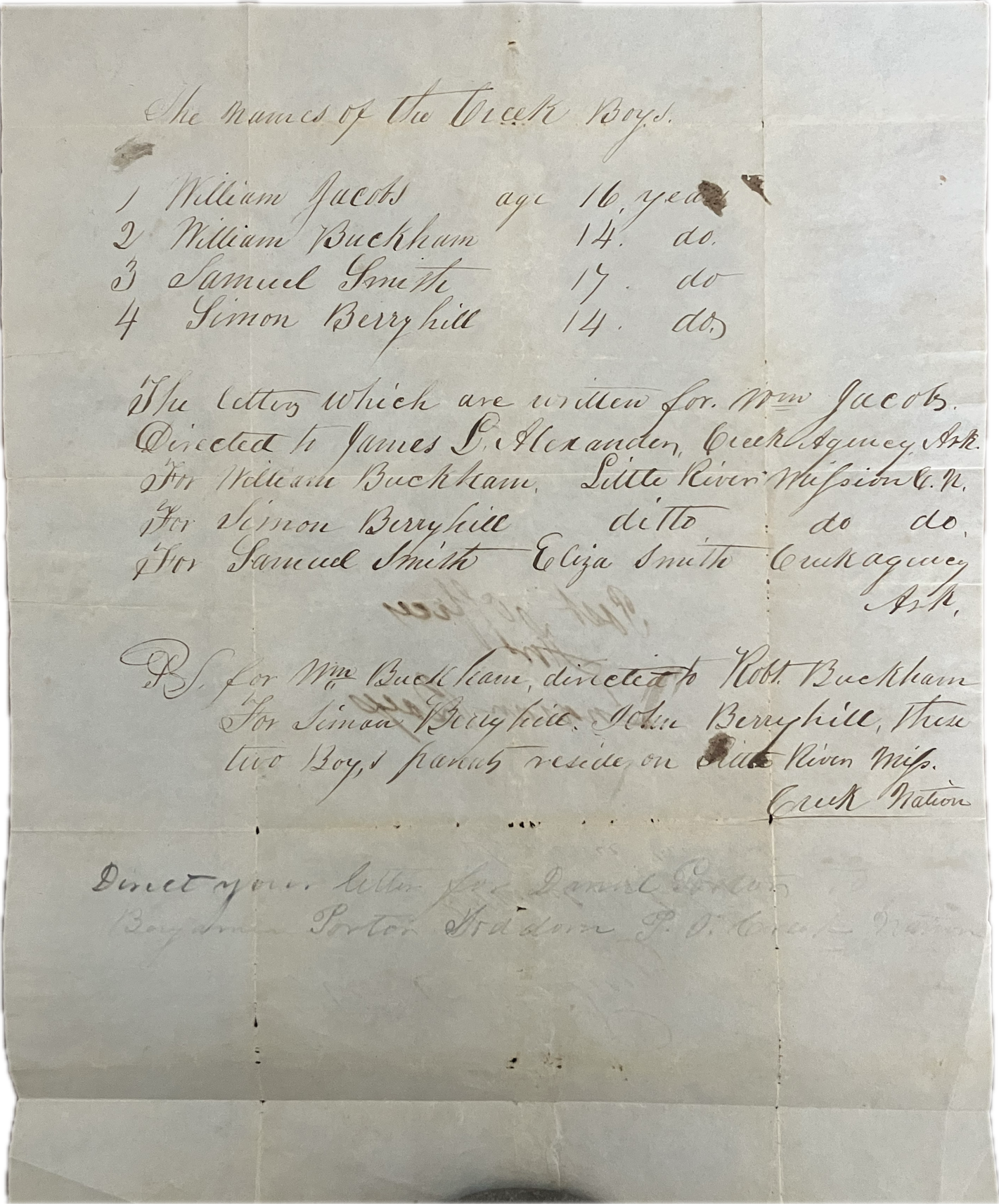

"Post Offices for Indian Boys": instructions for forwarding letters written for "the Creek Boys."

[Fairway, Kansas]: [c. 1844-1850]. Single leaf measuring 245 x 200mm with manuscript text in two hands to recto and address docketing to verso. Three vertical and five horizontal foldlines with minor soiling and separation along them; sheet remains whole. An undated manuscript with postal forwarding instructions for four children removed from their parents in Arkansas and held at the Methodist Shawnee Manual Labor School in Kansas, the docketing to the rear includes the name of the Rev. Edward Peery, who superintended the school from 1844-1850 and thus helps us narrow down the document's timeline. Founded in 1839 by the Rev. Thomas Johnson, an avid proponent of slavery, and run by Peery, the school and its history are often documented and discussed through the lens of its white overseers. This is largely because while documents about their lives and work survive, very few materials regarding its young Native American residents still exists. Thus, this small document provides an important opportunity for researchers to learn more about the names, identities, and families of four such "students," to uncover further information about their tribes and removals, to study or seek information on their survival and future lives, and to examine the seemingly small infrastructural detail of posting mail that reveals a wider system designed to separate the boys from their tribes, families, and cultures.

Native American activists and members of the Truth and Healing Commission have noted that much of the Methodist Shawnee Manual Labor School "history is told via one man, Thomas Johnson, a Southern slaveholder who arrived in what was called Indian Territory in the late 1820s with Methodist missionaries to 'rescue the savages of our wilderness from their states of barbarism'" (Plake). The recipient of funding from the government and the Methodist Church, Johnson focused his attentions on the Shawnees, who "had already made the grueling relocation from their Eastern homelands after the Indian Removal Act of 1830" -- a tragedy which left these peoples vulnerable to the "coercion and collusion" of a missionary group that asserted they would give the children a better life (Plake). Under Johnson's structure, as enacted by Peery, the children's hair was cut, their names altered, and their languages forbidden. In addition to time in the schoolroom being forced into English language and Christian learning, the "150 boys and girls from more than a dozen tribes" would be forced into manual labor alongside the enslaved people Johnson had placed on the property (Plake). Though students were given two annual visits to their tribes during harvest, the mission's annals reveal that "many families wanted their children to stay at home," but faced repeated removal as the new term began (Shawnee Mission Annals). As Chief Ben Barnes noted in a recent interview, the surviving structure of the school bears witness to the trauma children faced. "We can still see carvings on the wall, left in the windowless attics where children were forced to sleep in hot summers and cold winters. These children matter. Their stories matter" (Saving Places).

Part of recovering these children and their stories is through the preservation and study of seemingly simple documents like this. In a single sheet, the superintendant Rev. Peery receives information on four "Creek Boys": "1. William Jacobs age 16 years 2. William Buckham 14 3. Samuel Smith 17 4. Simon Berryhill 14." In the paragraph that follows, we learn that all four boys, though Creek, are not necessarily from the same place. The mailing instructions for their letters to reach home must go through separate post offices or agents where their families will be able to receive them. It also appears that the letters may not be entirely written by the boys themselves, but under some kind of supervision or "for" them. "The letters which are written for William Jacobs directed to James L. Alexander, Creek Agency Ark[ansas]. For William Buckham, Little River Mission -- For Simon Berryhill ditto --- For Samuel Smith, Eliza Smith, Creek Agency Ark." An addendum reads: "PS. for Wm. Buckham, directed to Robt. Buckham. For Simon Berryhill John Berryhill, these two Boys' parents reside on the Little River Miss., Creek Nation." Beneath this, in a barely surviving pencil addition in a different hand: "Direct your letters for Daniel Porton to Benjamin Porton 3rd Dorm PO Creek Nation." Living at reservations and on missions in Arkansas, these children and their parents faced convoluted barriers for contact in the periods between home visits. And the process appears to have been supervised and controlled, with letters sent or doled out through third party administrators.

Further research could be conducted on these boys and their families. Few digital traces exist; however, the papers of William Buckham's guardian Robert Buckham are held at Cornell's Native American Collection, for example, and other primary sources are preserved through the Shawnee Mission Annals. The US Census Bureau has further information on the shifting practices of documenting Native Americans in the census, as well as the sites of other tribal and federal records.

*As part of our Community Alliance Project, a portion of proceeds have gone to the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.*

(204)