Scandalous memoir writer Catherine Jemmat presents her audience with a biting critique of the patriarchy in Essay in Vindication of the Female Sex

[DV Survivors] [Scandalous Memoirs] [Sex Work] Jemmat, Catherine.

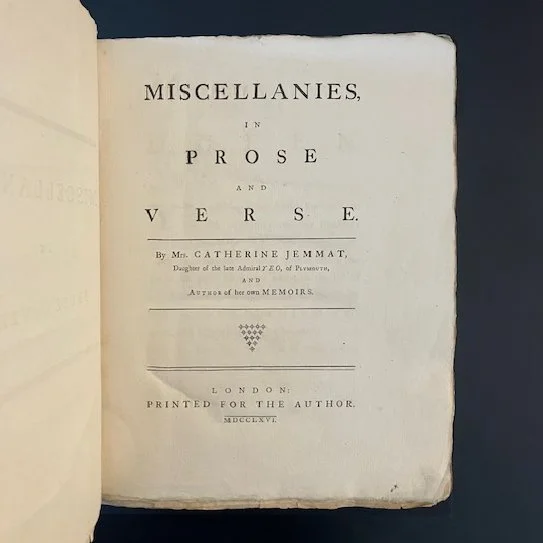

Miscellanies, in Prose and Verse. By Mrs. Catherine Jemmat, daughter of the late Admiral Yeo, of Plymouth, and author of her own memoirs.

London: Printed for the author, 1766. First Edition. Original publisher's quarter paper over drab boards with handwritten spine label, measuring 290 x 225mm and collating complete: [16], 227, [1]. Spine largely perished and joints cracked with cords holding boards well. Some dampstaining and loss to paper of front board. Internally wide-margined, fresh, and unmarked. An unsophisticated example of this scarce collection by domestic abuse survivor and feminist writer Catherine Jemmat, housed in a custom black clamshell with gilt to spine. In the absence of ESTC, OCLC reports only 7 copies (of these, two in the US) and the title does not appear in the modern auction record. The present is the only example in trade.

Born in Exeter to a military family, Catherine Jemmat (1720-1766) was a survivor of domestic abuse, first at the hands of her father and then her alcoholic husband (ODNB). Taking to her pen for financial independence, Jemmat wrote articles for the Gentleman's Magazine in addition to publishing her Memoirs in 1762 and the present Miscellanies in 1766 (the popularity of which called for a second edition in 1771). For Jemmat, writing provided more than economic support however. It also allowed her a platform for discussing her interests in science or technology that many assumed were out of women's realm, for calling out abuse like what she had endured, for re-framing the scandalous story of her own temporary engagement in sex work, and for expressing her deep frustration with the social hypocrisy and legal precarity that shaped all women's lives.

Miscellanies opens with the traditional preface containing apologies and thanks -- an act which the author acknowledges tongue-in-cheek by explaining "introductions are become so customary...that I may not deviate from the track marked out by all my predecessors in the writing way." The poems and essays contained within are much less customary. Early on two poems, Ode on Science and On the Invention of Letters and the Utility of the Press, celebrate human advancement in understanding the natural world and creating methods for documenting and sharing innovations for public benefit. These hit an optimistic note, and a logical one. These run up against several other works in content and tone, notably The Rural Lass with its jaunty rhyming lyrics and story of a young woman hoping to fix her future with the town rover, and Account of a Clergyman's Family, a prose essay telling of how the death of a reverend with poor financial planning ends in the ruin and poverty of his widow and daughter. Like technology, men have also invented these systems; unlike technology, they spread harm rather than good. Yet Jemmat makes it clear than women are not powerless. Judith's Speech to the Elders of Israel gives her a means for conveying this. She uses the Biblical leader's forcefulness and anger to convey her own as well as to ensure that her readers are attentive for what comes next: "Attend ye fathers, nor too rashly run, To meet the evil which you may still shun." Because at the heart of Miscellanies is its most overt and important feminist message, titled Essay in Vindication of the Female Sex.

Appearing in print 26 years before Mary Wollstonecraft's work of a similar title, Jemmat's Essay in Vindication of the Female Sex attacks the dangerous hypocrisy surrounding how men and women are valued based on their sexual histories and reputations. Mincing no words, she explains, "I have been making some reflections on that great disadvantage which the female sex experience if they are once so unhappy as to be branded with the title of prostitute; and I cannot by any means find out the least reason why they should be accounted more ignominious than the male sex who most frequently are the cause why they are rendered so disgraceful...an illicit behaviour ought to be considered equally unjust in either sex." Yet women bear the brunt, even as men participate in sexual activity and even as patriarchal systems place women in precarious situations. Jemmat's argument is not merely a rhetorical exercise. It emerges from her own life. In her 1762 Memoir, Jemmat publicized her "doomed quest for domestic happiness"; and though it was advertised as "a tragedy of a fallen woman," the book refused to conform to audience expectations by featuring her initiation into sex work (Breshears). Instead, Jemmat "modified the structure of the 'scandalous memoir' and provided a model for later memoirists" by situating "the scandal of her text not as her sexual fall, which she never narrates, but her abuse and abandonment by her relations" (Breshears). Jemmat makes a similar move here. Though she touches on her own history ("I am an unhappy woman who have deviated from the strict paths of virtue") she does not express shame; instead, just as her memoir recast what constituted a moral failure, so too does her Essay. It is indeed the longest piece in Miscellanies and the most powerful.

Miscellanies in Prose and Verse, like much of Jemmat's work, have only just begun receiving scholarly attention. And while her Memoirs have been the main focus, this compilation certainly deserves greater analysis.

Women's Print History Project. Breshears 65. (62)