A clandestine erotic book intended to titillate younger adult readers hides its intent by claiming to offer parental advice against immoral acts

[Crime & Punishment] [Class & Gender] [Clandestine Erotic Literature] Smith, Mr. and Mr. Allen, Mr. Wikes, and Mr. Lorrain

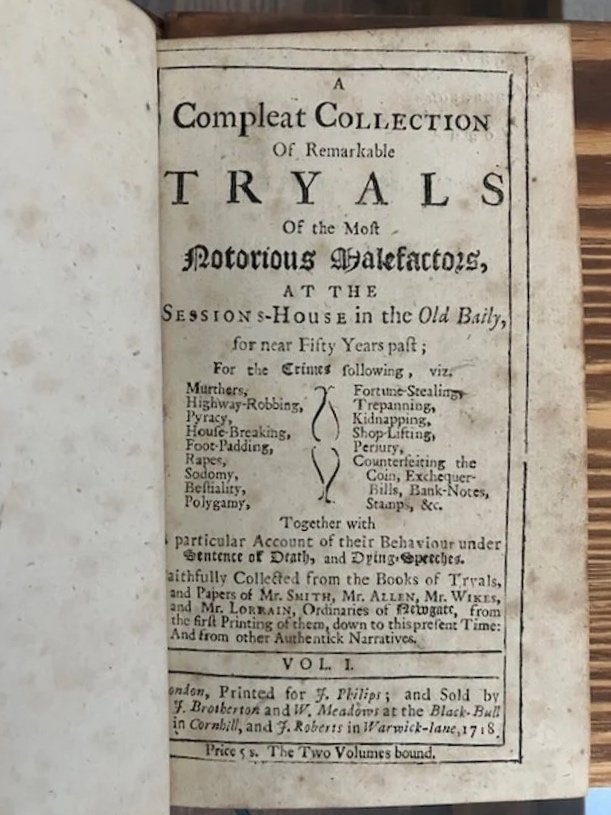

A Compleat Collection of Remarkable Tryals of the Most Notorious Malefactors...Together with A particular account of their Behaviour under Sentence of Death, and Dying Speeches...(in 2 vols.)

London: Printed for J. Philips and Sold by J. Brotherton and W. Meadows, 1718. First Edition. Nineteenth century polished calf with gilt and morocco to spines. All edges stained red. Brown endpapers. Measuring 155 x 85mm and collating complete: [12], 434; [4], 344. A square, bright set with discreet repairs to the lower spine ends of each volume. Light toning and occasional foxing throughout; several pages trimmed close along the upper margins in volume I with no loss to text. Early owner's blindstamp to upper right corner of each title page as well as to page 99 of both volumes. Initially released in two volumes in 1718, A Compleat Collection gained an additional two volumes in 1720 and 1721. ESTC reports no complete sets of four volumes with the exception of Harvard; while Aberdeen, Trinity, and the BL each report having volumes 1-2, all other listings in North America and the UK report no more than a single volume of the set. The modern auction record reports only three appearances of the text and none including the final 1720-21 volumes: 1978, 1900, and 1893 (a bookseller's notation on the front endpaper of volume I notes provenance from the Beckford sale of 1883, which preceeds Rare Book Hub recordings). The present is the only example in trade.

Presenting this extensive catalogue of murders, robberies, piracies, assaults, sodomies, polygamies, fortune-tellings and affairs to the reader, the authors suggest they make possible the "Discouragement of Immorality and Irreligion First, to young Persons themselves; and Secondly to those to whose Care they are committed in minority." Like laws themselves, the Preface argues, the recounting of crime and punishment is designed as a deterrent to others within the community who might face temptation, especially those "young Persons." In this sense, the authors reveal something else about their publication's intent: that by advertising the types of crimes that titillate early sexual curiosities and that speak to youthful frustrations about the confines of economic class or gender, the text will draw to them a new market of young readership typically untouched by such publications.

What follows across the volumes are vignettes just lengthy enough to present a scene that sets fire to the imagination. Some of the tales are predictable enough, appealing to the youthful interest in sensational fiction. In The Tryal &c of Sir John Johnson for Stealing Mrs. Wharton, readers encounter the titled man with debt who seeks to swindle a series of young women whose fortunes might bring him financial relief; and they learn of his failed attempt with Miss Magrath and his successful elopement with Mrs. Mary Wharton, "an heiress of considerable means," which landed him in prison. The Tryal of Margaret Marteel for the Murder of Madam Pullen offers a reminder that women can be just as dangerous as men. In this case, the French creole Margaret Marteel robs the Englishman Paul Pullen and slits the throat of his wife Elizabeth, whose jewels and clothes she desired.

Tucked within these more predictable narratives, however, are those that would shock readers and, for many, introduce them briefly to sexual practices and desires they might not encounter within the heteronormative stories presented by their elders. To wit, The Tryal of Mary Prince depicts a maid who, in spying on the maid who lives in chambers below her, witnesses an act of bestiality: "she saw the Prisoner sitting in a chair by the fireside leaning backwards...she took the Dog to her, who she said acted to her as with a Bitch"; and the Tryal of Captain Rigby for Sodomy graphically describes the encounter between the Prisoner and a man with whom he was caught during fireworks, who "put his Privy members into [the man's] hand, kiss'd him, and put his Tongue into his Mouth." These seem much less likely to fit the writers' ostensible mission of educating young people against immoral action and urging conversation with parents; rather, they seem likely to kindle curiosity, spark illicit conversations among the young readers, and urge the continued purchasing of the text by new readers as word spread.

Not in the Register of Erotic Books.