In which a father and daughter potentially conspired to hide the sale of land from an abusive husband and ensure funds for her future safety

[Women and Property Ownership] [Lenape Peoples] Penn, Laetitia with John Mifflin and James Logan.

Mortgage of John Mifflin to Laetitia Penn for lands purchased from William Penn's only daughter.

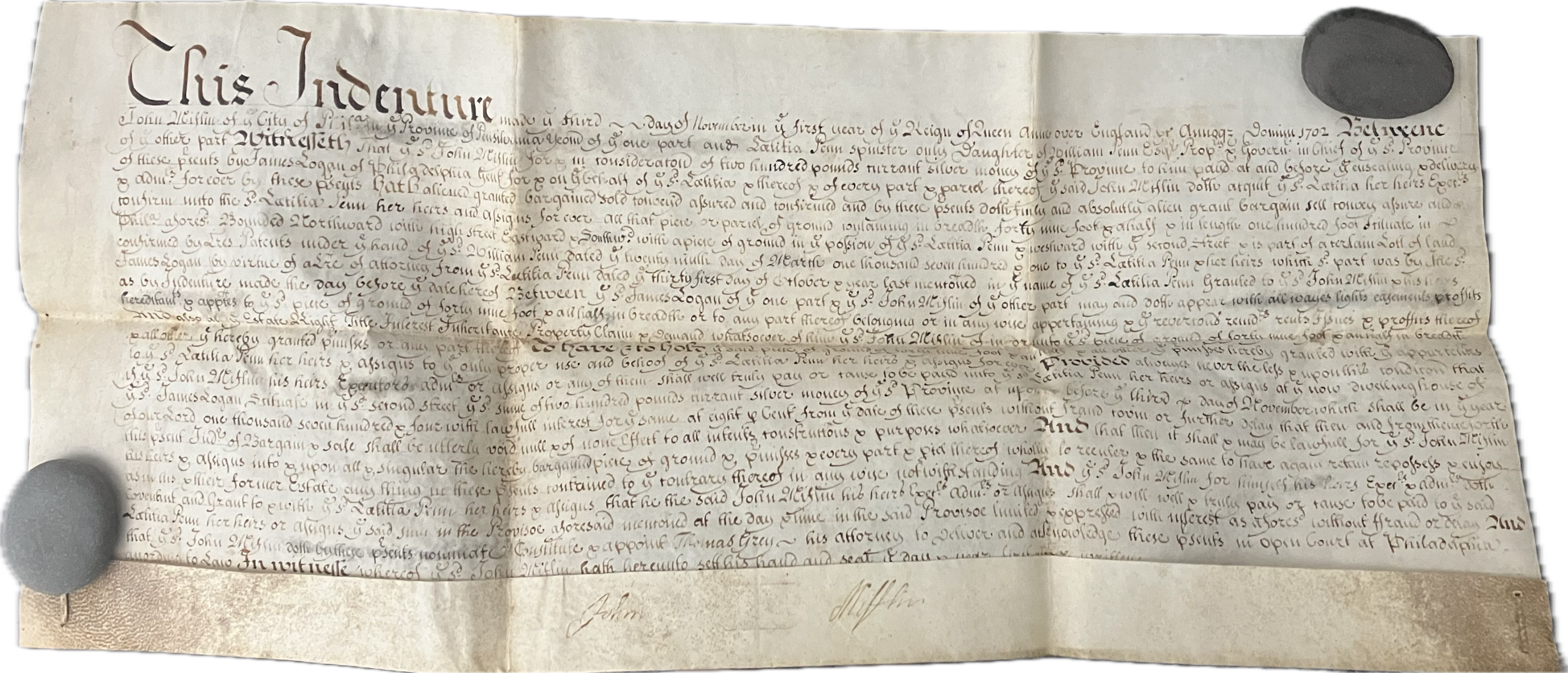

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Colony: 3 November 1702. Contemorary vellum with manuscript text in an italic hand to recto and docketing in secretary hand to verso. Measuring 600 x 26mm with long horizontal central foldline and three vertical folds. Vellum a bit age toned and stiff. All text legible, with several contemporary corrections present. Docketing to rear notes that this is the Mortgage of John Mifflin as well as including an affidavit from attorney James Logan. Conveying roughly an acre of land from the corner of Second and High Streets for "two hundred pounds silver money" (approximately $60,000 today), this colonial mortgage agreement not only gives us information into the Penn family’s dealings and how its second generation transferred Lenape land for wealth; it also hides a secret, about how William Penn and his daughter Laetitia may have concealed real estate profits from her new husband in order to create some level of financial protection for her in the marriage.

"In 1682, William Penn arrived to claim the lands guaranteed him by the King of England, Charles II. The land was dedicated for persecuted Quakers but was already the homeland of the Lenape people" (ALA). In line with Quaker beliefs of goodwill, Penn established "relations with the Lenape through the Shackamaxon agreement, that bought out their lands but allowed them to retain certain villages and locations that could not be sold" (ALA). This guarantee stood until Penn's death in 1718. His son, Thomas Penn, who had outlived his brothers, "gave a portion of the shares to his own son, John Penn, who became the chief proprietor of the colony (Historic Pittsburgh) and who overthrew his father William's treaty in favor of the Walking Purchase of 1737, which defrauded the Lenape "of almost a million acres of traditional land" (ALA). The relationship of Penn’s sons to the land is well documented.

The relationship of Laetitia Penn to her lands is much less obvious. On arrival to the colony, Penn had deeded roughly 5,000 acres of Philadelphia to his only and much-doted-upon daughter from his first marriage, Laetitia Penn (1678-1746), a "lively and strong-willed girl" (Whelan). Upon her own insistence, Laetitia had traveled in 1699 at the age of 21 to join her father in Pennsylvania; but this sojourn lasted only a short while, as she returned with her father and her stepmother in 1701 to England (Certificate of Removal for Laetitia Penn, Bulletin of the Friends Historical Society). After a brief engagement to a local man, William Masters, Laetitia broke with him because her father “felt his daughter should marry someone better educated and better born…On August 20, 1702, at a Friends Meeting, Laetitia Penn married successful merchant William Aubrey” (Whelan). With a new husband came a new legal identity as feme covert and his property, which would transfer ownership of all future wages and inheritances to Aubrey. This undermines the opening premise of the present land indenture, which suggests that Laetitia is an unmarried “spinster” with legal feme sole status when she decides to sell a parcel of her land. "This indenture made the third day of November...1702, between John Mifflin of the city of Philadelphia province of Pensilvania [sic] of one part and Laetitia Penn, spinster, only daughter William Penn, Esq. governor and chief of the province, of the other part, witness that John Mifflin for the consideration of 200 pounds silver money...ensuring delivery of these presents bye James Logan of Philadelphia, Gentleman, on behalf of the said Laetitia thereof, and every part & parcel thereof the said John Mifflin doth acquire and acquit the said Laetitia [and] her heirs forever."

For the modern equivalent of $60,000 Laetitia relinquished roughly an acre of land in the township -- and she did so before her brother violated the treaty with the Lenape. It is also an extremely small parcel compared to the large portion deeded by her father. And here, questions emerge about the extent to which Pennsylvania colonists would have known about Laetitia’s marital status, and whether the small sale might have been insignificant by design.

Shortly after his daughter’s marriage, “Penn had cause to regret his actions at length. A contemporary source notes that ‘Aubrey seemed to imagine that it behooved his father-in-law to furnish him with the means of support and made imperious demands for large sums of money at frequent intervals.’ Aubrey also insisted on money from the sales of Pennsylvania land be given to him. According to Penn, he was not polite about it. In one of his letters, he pointed out that he had given his son-in-law 1,100 pounds [ approximately $327,000 today] and was being treated in a ‘mad and bullying way’ and ‘his rude and tempestuous conduct’ infuriated him…Rumors persisted of hellish fights between Laetitia and her husband over money until his death in 1731” (Whelan). By that time, her father had died nearly bankrupt, and her brother Thomas was on the verge of defrauding the Lenape.

Within a system that defined a woman’s property and income as her husband’s, few options existed for protecting women against unscrupulous and abusive mates. One option was, during a woman’s adulthood when she gained legal, independent feme sole status, to establish pre-marital property that could remain under her control. “The stricter and more universal application of coverture in early America under colonial rule” meant women lost more rights in marriage but had certain feme sole protections that ensured the treatment of pre-marital property required “the signature of a wife before a wife’s property could be transferred into joint ownership in marriage” (Walsh). It seems possible that in the months between Laetitia’s wedding and this transfer of land, she and her father designed a situation in which a small enough portion would be sold, while there was no record of her marriage yet in Pennsylvania, in order to ensure that she had at least some funds of her own in the face of Aubrey’s demands. Laetitia outlived her husband by fifteen years, and we have not located signs of bankruptcy or debt on her part.